UM YUMNA’S EVICTION

The suburbs: a destination for the city’s most vulnerable

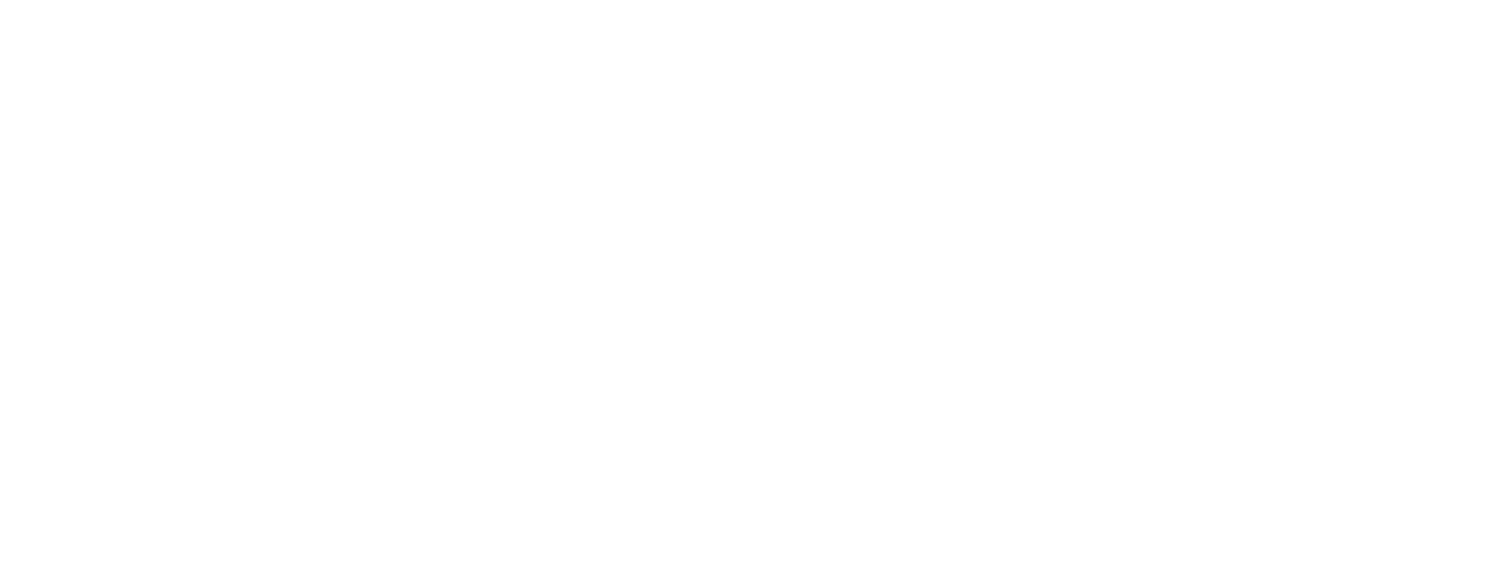

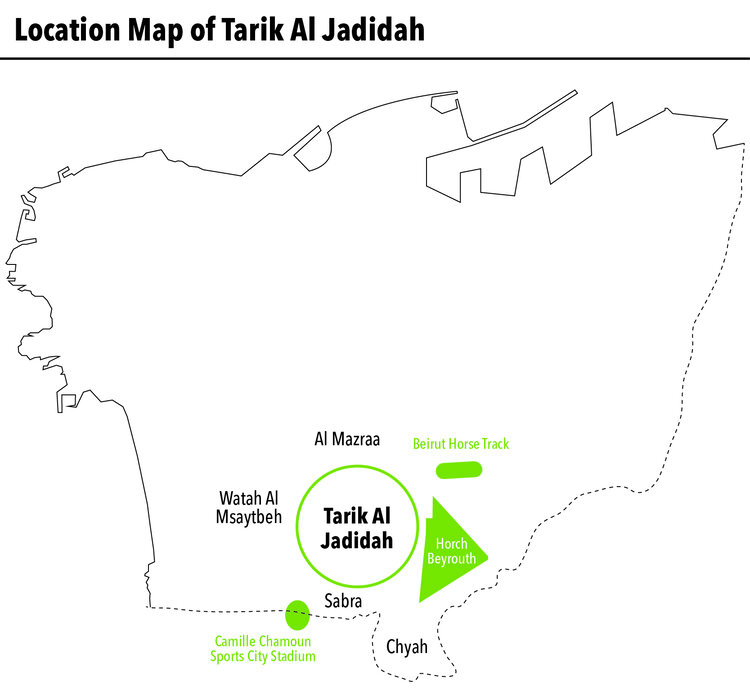

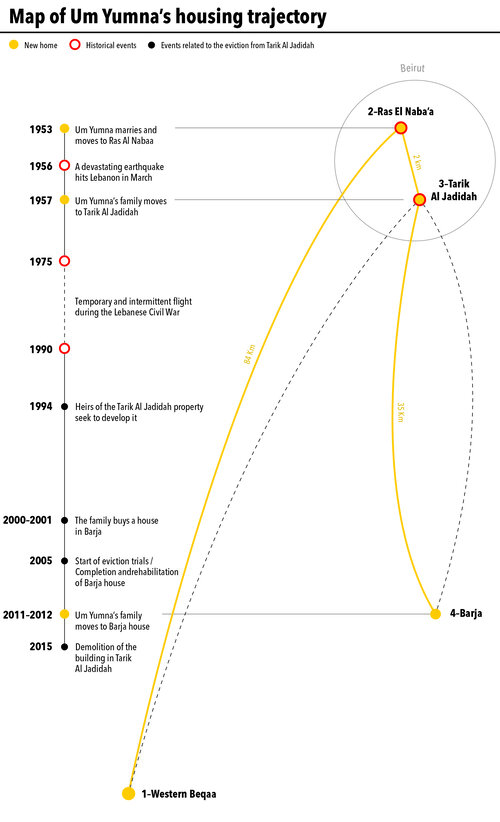

Um Yumna was 14 years old when she moved from Beqaa to live in Beirut. She had married a young Berjaoui [1] man who worked at a company in the city, and they settled in one of the small homes of Ras Al Nabaa. That was in 1954 or 1955; she no longer remembers precisely. The following year she would give birth to the first of six children, then the second. A year or two later, the country would be shaken by a series of earthquakes. Six thousand houses were destroyed in the 1956 earthquake. Entire villages collapsed in Chouf Al Aala and Iklim, and Um Yumna’s house in Ras Al Nabaa came apart. In 1957, the young family packed up their belongings and moved. At the time, Um Yumna did not intend to spend the next 55 years of her life in that little three-room house atop Zreik Hill in Tarik Al Jadidah.

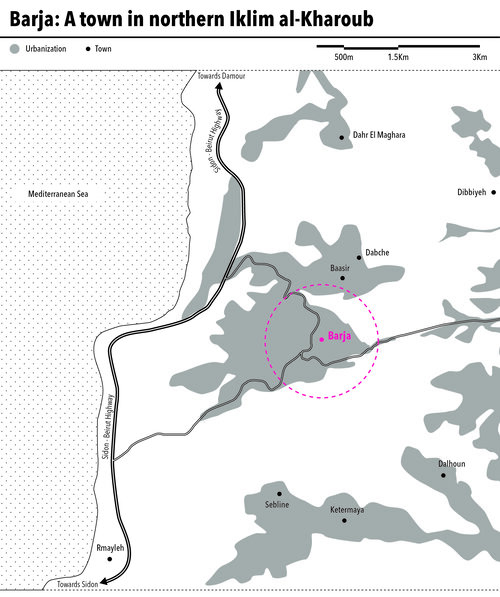

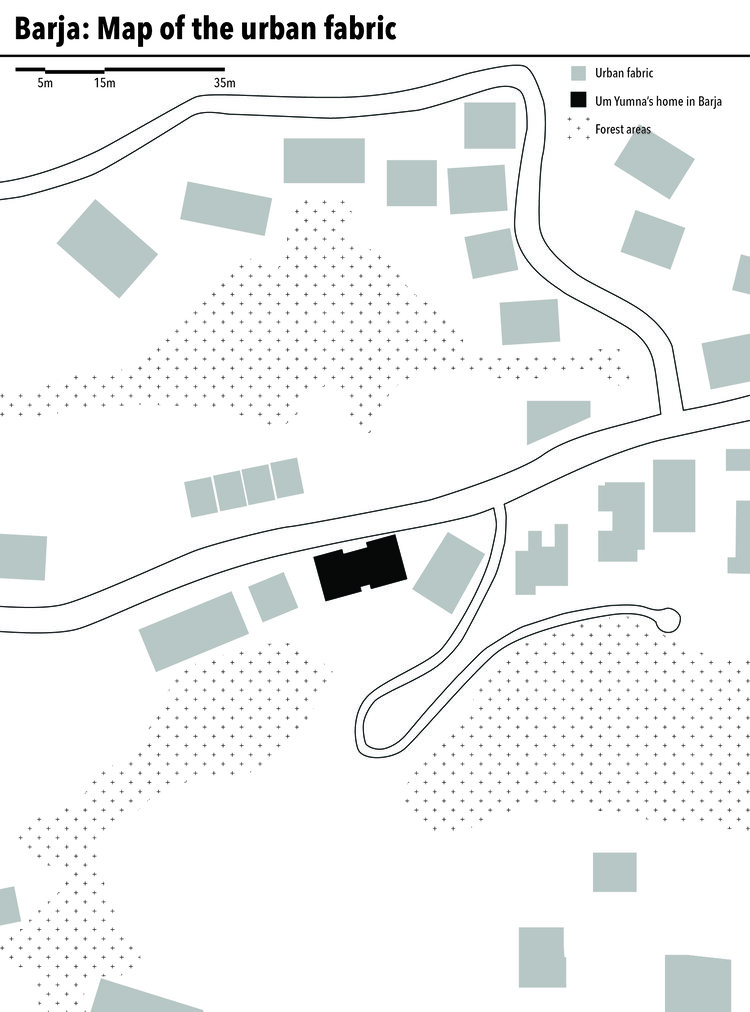

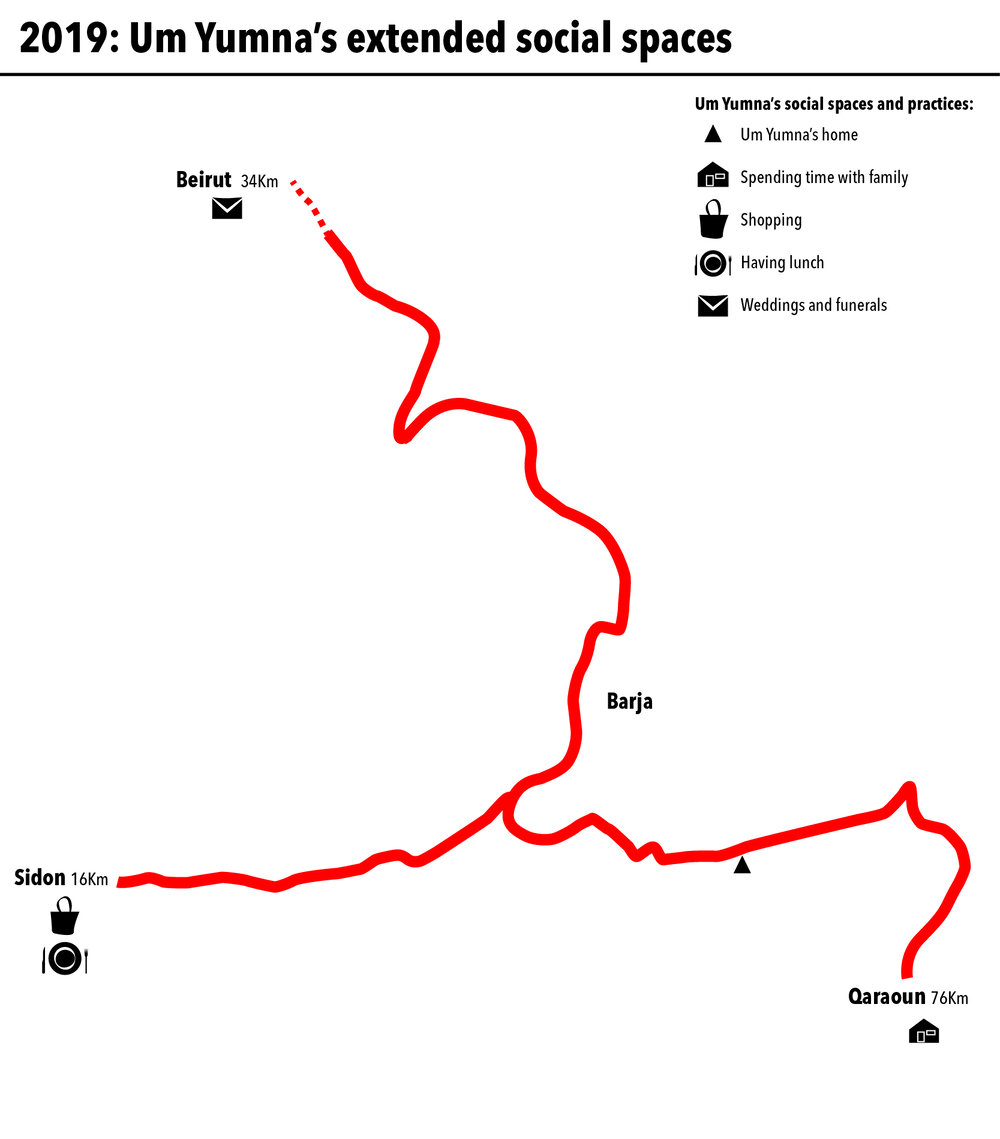

Today, from her home in Barja, Um Yumna reflects on her housing trajectory. She describes how her eviction from her house in Tarik Al Jadidah affected her, and how she tried, as an elderly woman, to oppose this eviction. With grief, she explains her struggles of belonging and adaptation in the face of the spatial, social, and economic changes she has gone through.

[1] Berjaoui e.i.Hailing originally from the town of Barja south of Beirut